“What we know about who to be who we are comes from storytelling. It’s the agents of our imagination that really shape who we are,” award-winning novelist Chris Abani once said in his Ted Talk titled, Telling Stories from Africa. As Africans, tradition is finely woven into our culture landscape. A tradition so embedded in our history and present, rich with generational sharing of stories, and one of the many cultural aspects that bind us as a people. Used as a tool to foster social cohesion and preserve heritage, homage has been paid to tradition practices – which include elements of folklore, poetry and poetic proverbs, to name a few – through literature, song and visual art. More recently, Black Panther, one of the top 10 highest grossing films to dates, gives a nod to culture throughout its provocative narrative and features storytelling by elders to younger characters. While in literature, award-winning novelist, intellectual and feminist Chimamanda Adichie Ngozi laces lyrically her books, from proverbs in Purple Hibiscusto storytelling in Americanah, proudly alluding to Ibo “orature” (or literature).

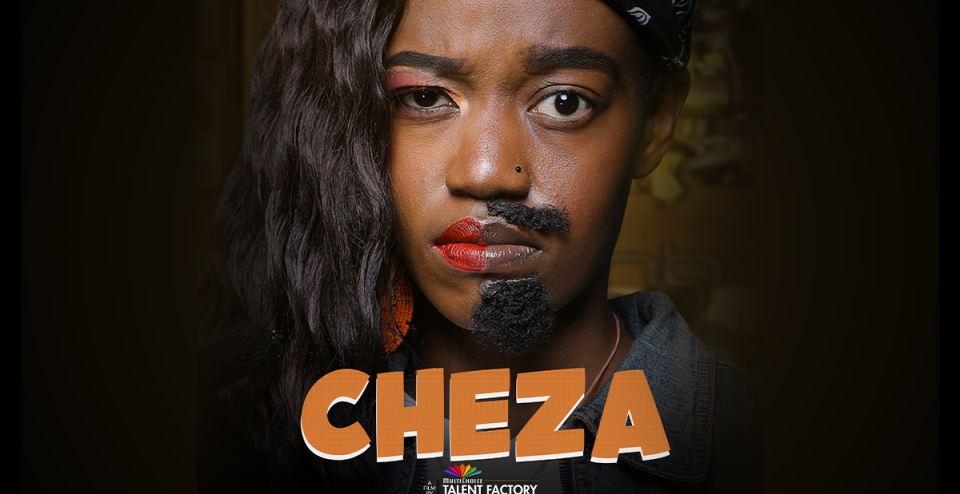

“One thing that we do have is stories,” says film and TV pundit Berry Lwando, whose work in Zambia’s broadcasting industry spans decades. And it’s the continuation and celebration of tradition that Berry says is at the foundation of the work that he has recently embarked on as Academy Director for the MultiChoice Talent Factory (MTF) in southern Africa, which includes the countries Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. MTF is a brand new initiative dedicated to training 60 individuals from 13 African countries to hone their film and television production skills in a year-long funded programme supported by MultiChoice Talent Factory academies hosted in Kenya, Nigeria and Zambia.

“We have a huge storytelling tradition. Most of us, from generation to generation, would have been told stories by our great grandmothers or uncles, and sometimes by the fire light. But what we don’t have here is a cinematic tradition and don’t quite have the skills to put that story together in the manner that would fit on a television screen, and that has challenged.”

A former director of programmes at the Zambian National Broadcasting Corporation, Berry has been in the broadcasting industry from 1989 working at various levels from camera to director and producing, and is encouraged to develop skills for African creatives to share African stories on screen, without relying on video entertainment from outside the southern region, like the United States, Nollywood or South Africa.

“We haven’t really had the proper skill set that would transform creative storytelling abilities on screen to packaging it through creative camerawork and sound that is acceptable for television. [It’s not nearly up to the level where we can turn it] into an industry that would create a sustainable business.” From funding issues to a lack of adequate training opportunities in the area, Berry highlights the roots of the issues plaguing the video entertainment industries in the southern region, which co-exists alongside major industries such as Bollywood, Hollywood, South Africa’s film/TV industry and Nollywood, which – in data released this year – showed to “be a $6-billion sector worth about 1.2 per cent of the economy”, according to the Globe and Mail. While South Africa contributed R5.4-billion to the gross domestic product during the 2016/17 financial year.

“The industry in the south has big gaps. South Africa has kind of filled those gaps and proceeding pretty well in terms of quality of products that they create. But the rest of southern Africa is still getting there.”

As Berry gears up to oversee the training of 20 learners from the seven African countries, he notes that each one of the countries have their own set of characteristics, distinct histories, cultures and languages, to name a few. “There’s different times that the countries became independent, which meant the shedding of colonial understanding of things and striving towards independence.” While at the same time, illustrating the similarities especially relating to the development of the film industries across the region. “Southern Africa actually has a lot of similarities. There are levels of oneness relating to the migration of the people, such as the Nguni people migrating from South Africa right through Zambia, Mozambique and Malawi for instance. You can also see that shades of the languages that are spoken across the regions”].”

Despite this, there is undoubtedly strides that have been made in the film industry across the regions. The spread and proliferation of film festivals in the region are fostering an on-screen culture for creatives and MultiChoice’s Zambezi Magic has created additional platforms for filmmakers to showcase their work and has, among other functions, boosted the television industry by creating jobs and commissioning local products in six countries across the region.

But more is needed to develop this industry. Across the region, on-screen practitioners and researchers raise ire at the lack of on-screen-specific organisations or basic policies and frameworks that are essential to maintaining and developing this industry. In a paper by Nyasha Mboti, the associate professor at the University of Johannesburg, writes about the Zimbabwean film industry. “The use of the term ‘film industry’ does not, and ideally should not, mean a single thing to everyone. If one applies the definition used in the economically privileged contexts of film industries in the United States and Europe, or even in neighbouring South Africa, there would be no Zimbabwean film industry to talk about.”

Comparing it to other industries, the former lecturer at the University of Zimbabwe highlights the paucity of data on the local film industry and other challenges the industry in Zimbabwe faces. “There is also no central film organisation, such as a Film Commission, tasked with collecting systematic intelligence on the industry. In European countries such as France, Germany and England numerous state and private bodies exist for funding local industries.”.”

A few filmmakers from across the region share Nyasha’s views. Speaking on Mollywood, Malawi’s film industry, Film Association of Malawi, or Fama, president Ezaius Mkandawire expounds. “Malawi has what we can call a budding film industry. We have an industry that is still a baby. We do not have spaces of distribution in the country like most developing industries in the world do. Malawi only has a single film festival that is struggling for money to have a meaningful impact. The country also has very few cinemas. Tailor- made spaces to market films are non-existent and this is hampering the growth of the industry.”

While countries like Namibia, which has been a location for major international blockbusters like Mad Max and The Mummy, was reported in 2016 to only have produced one feature film Katutura, since Namibia’s 25 years of independence. According to a CNN story on the local Namibian on-screen industry, “National TV channels have so far played host to foreign dramas, which are much cheaper than producing their own content. With no funding available for local filmmakers, Namibian stories have remained absent.”

Despite the prevailing challenges, there have been exciting and impressive developments in the industry. “These seven countries are active in different ways. Zimbabwe particularly is moving very strongly towards an acting tradition, and trying to create a creative screen community and develop their own genres,” Berry points out. And in Mozambique, for example, animation studios FX Lda just released its trailer for the upcoming feature film Os Pestinhas,touted as the first animation feature film from Mozambique by Mozambicans. The country is also home to numerous film festivals.

“I’m interested in hearing about Africa’s stories, and images that show a positive progression of the African story,” says Zimbabwean documentary filmmaker Cosmo Itayi Zengeya.

Based in the capital city, Cosmo’s films explore themes such as culture, displacement and politics, such as his film Much to the Land of Promises,which screened across Africa, the Middle East and Europe. “In the past, we had the colonial films that were dominant on our screens but the narrative is changing because a lot more African people are getting into filmmaking. We are telling our own stories. I’m interested in seeing more African narrative on our big screen. Like Black Pantherand Sankofa, the real Pan-Africanist and African stories.”

Sharing his perspective and experience of the filmic landscape of Zimbabwe, Cosmo is both hopeful and concerned about the industry. As a filmmaker, Cosmo says there are obstacles faced by creatives in his genre of work and says because “we need to put food on the table”, non-governmental organisations who commission work or wedding videos help filmmakers stay financially afloat. Besides working on documentaries and writing two feature film scripts, Cosmo relies on creating short videos for news companies like Al Jazeera and New York Times.

Cosmo highlights progressive filmic movements within Zimbabwe, like the Women’s film festival hosted by International Image Film Festival and Zimbabwe International Film Festival, which aims to increase the visibility of women in the male-dominated industry, and talks about how political changes in the country has positively affected the film industry. “It was difficult to make films during the Mugabe era – you’d be asked where you are going or what you are doing with that camera. There was this fear and gatekeeping. But it looks like things are changing now.”

Despite this progress, obstacles affecting the southern region are not lost on Zimbabwe. “Issues here are many and varied, and specific to individuals. But the main one is funding. There’s no funding organisation targeting film.” Offering a remedy to the problem of funding, Cosmo looks to co-productions when creating on-screen entertainment. “We could partner with South Africa, Zambia, Mozambique and even abroad, in the US and countries in Europe. Co-productions lessen the burden of funding. I believe, filmmakers abroad have easier access to funding because there are film organisations there. I think we also need a film commission, or a regional one that would assist filmmakers to get access to money to make their films. Here in Zimbabwe, we also could use a policy specific to film.”

As steps are being taken in the right direction within the region’s on-screen entertainment, much more is needed to raise the market’s level.

Berry looks to the MTF as a source of propelling the industry through training and skills development. “The big plan for MultiChoice is to ignite the creative industry. By looking at the different aspects of the creative industry, we aim to get people within the screen industry to a position where they can actually thrive, and to where producers can take advantage of the entire value chain.”

Emphasizing the importance of tradition in Africa and preserving it into the future, through expression across different mediums such as video, Berry says, “What MTF is trying to do in southern Africa is to enhance the skill sets and capacities of creatives, and we aim to get people to focus on the narrative. We believe we’ll be able to empower our people in southern Africa to tell their stories.”

Stay ahead of the conversation

Get yourself up to date with your industry news